Performance and Change

Posted by agilecmmi on Aug 7, 2011 in Change, Discipline, Improvement, Performance, SMART, objectives, operations, pareto principle | Comments Off

Over the past weeks I’ve come in touch with several companies with the same exact challenge. Though, to be sure, it’s nothing new. I encounter this challenge several times each year. Perhaps, even following Pareto’s principle, 80% (or more) of the companies coming to me for improved processes have a variant of a form of distress that accounts for no more than 20% (or less) of the possible modes of distress.

In particular, the challenges are variants of a very basic problem: they want things to change but don’t have an objective performance capability to aspire towards. Put another way, they can’t articulate what it is that their operation cannot currently accomplish that they’d like their operation to be able to do once the changes are put in place.

I’ve mentioned “SMART” objectives before. Here’s another application of those same objectives, only now, they show up at a higher level within the organization.

Executives of the organization often confuse “SMART” objectives with “fuzzy” objectives. By “fuzzy” I mean objectives that appear to be “SMART” but aren’t, and, the fuzziness obscures the situation so as to over-render the truly uninspiring nature of the objectives as being substantial accomplishments. In fact, fuzzy objectives are not actually objective (lacking a solid way to measure accomplishment), or, are easily “gamed” (data or circumstances can be manipulated), or, are very deep within their comfort zone – or the opposite – are ridiculously unreachable (achievement is too easily attained or excused for not attaining), or, are indicators of task completion rather than indicators of actual outcome changes (don’t actually achieve anything but give the appearance of making progress), or, aren’t tied to actual increased capabilities/performance (don’t cause anything to change that anyone cares about), or, are dubious achievements that can be accomplished by simply “rowing faster” (working harder by working longer hours or assuming too much risk or technical/managerial debt), and so on.

These same “fuzzy” objectives are frequently couched in deceptively goal-esque achievements such as achieving a CMMI rating, or “getting more agile”, or getting ISO 9000 registered. What I noticed among the recent crop of companies with these issues is that they shared a particular set of attributes. They were after “improvements” but didn’t know what they wanted these “improvements” to enable them to do in the future that their current operation was preventing them from accomplishing. Sure, as in the case of CMMI, achieving the “objective” of a rating would enable the company to bid on work they currently can’t bid on, but that’s a problem addressed in two separate posts (here and here) from a while ago.

Digging a little further, I uncovered a more deeply-seated challenge for these same companies. In each case, they could not articulate what they actually wanted to be when they “grow up”. Closely related to not being able to explain how they wanted to be able to perform that their current operation precluded them from performing, they also couldn’t say whether they wanted their company to be leaders in:

- product innovation,

- operational excellence, or

- customer intimacy.

According to Michael Treacy and Fred Wiersema, in The Discipline of Market Leaders, every company must decide the ordering of the above three values and how to organize and run the company to pursue the value they’ve chosen as first, followed by the second, etc. Furthermore, and most seriously, leaders in the companies I visited were having serious issues. Sometimes in more than one area: delivery, quality, scaling, proposal wins, proposal volume, cost pressure, and so on. In none of the distressed companies were they looking at the performance capabilities of their operation. And, in none of the companies did they have metrics that gave them insight into the performance of their operation or helped them make decisions about what to change or how. In other words, they weren’t connecting their challenges to their lack of performance to the role their operational system of processes plays in that performance.

One thing that could help these companies climb out of the mud they’re in would be to simply and clearly define how it is they’d like to be able to perform that their current operations don’t facilitate, and, to define this capability in terms that represent an actual shift in how the operation functions. Changes for improved performance is not about adding more work, adding more bureaucracy, or making people work harder. Often, “working smarter” is easy to say but lacks substance. “Working smarter” actually shows up as changes in the operational and managerial systems that carry out the performance of the operation. A company that wants to perform better doesn’t need to add more work, or crack the whip louder, it needs to change how its operation runs.

One thing that could help these companies climb out of the mud they’re in would be to simply and clearly define how it is they’d like to be able to perform that their current operations don’t facilitate, and, to define this capability in terms that represent an actual shift in how the operation functions. Changes for improved performance is not about adding more work, adding more bureaucracy, or making people work harder. Often, “working smarter” is easy to say but lacks substance. “Working smarter” actually shows up as changes in the operational and managerial systems that carry out the performance of the operation. A company that wants to perform better doesn’t need to add more work, or crack the whip louder, it needs to change how its operation runs.

More about this is in my upcoming book, High Performance Operations, available now for pre-order and due out at the start of October 2011 or earlier.

A Tale of Two Companies

Posted by agilecmmi on Jun 26, 2011 in Class, Culture, Customer Satisfaction, Efficiency, Good Will, Happiness, Leadership, Performance, Psychology, Service, behavior, employee satisfaction, management, operations | Comments Off

Earlier this month I had the utmost pleasure to visit one of the most innovative, successful, ground-breaking and thought-provoking companies on the planet. I really wanted to immediately blog about them but was having trouble coming up with something more than an "I <3 ____" entry.

Earlier this weekend I had the utmost disappointment to patronize a company that provided me with such a contrast to the first company that I immediately had sufficient content to do justice to a blog post with something constructive. Little did I know that as I was amidst my experience and formulating this entry in my head, the latter company would be generating the exact sort of "proof" to support predictions I had planned to make about the company’s performance. As I write this, events are unfolding to practically word-for-word demonstrate my points for me.

I’m sorry this entry is very long… but you’ll see why soon.

The former company is growing at lightning speed in size, revenues, and profit. In The latter company has already pulled out of several markets and scaled back operations in others, is adopting tactics known to disenfranchise customers and seems utterly oblivious to it’s operation’s lack of efficiency.

Sadly, chances are the latter company will continue to make decisions that will negatively affect their outlook while the former company could easily be turning the latter around if the latter would bother to pay even the slightest attention the the cause-and-effect of their actions.

The former company, to a person, is keenly aware of what makes a satisfied customer. Their policies, hiring practices, operating values and reward systems are all consistent with and fully cognizant of what makes people (employees and customers) satisfied. Their people exhale good will and sweat fun.

The latter company seems to have scraped up some dusty "how-to" manual — probably chiseled in a cave somewhere — full of the best ways to be oblivious to the desires of humankind. Their policies — as evinced by the tactics and activities of their people — clearly convey that those who wrote them haven’t thought-through what people want or how people think; their operations manuals were written without ever considering how the people who’d have to follow them would feel about behaving as set-forth in those procedures.

The former company wouldn’t give a second thought to treat a customer with a level of service above and beyond what the customer may have paid to expect at any almost cost, while the latter company goes out of it’s way — to the point of introducing gross inefficiencies — to separate levels of service along artificial lines of "classist" service levels.

Finally, the former company would encourage its employees to invent ways to simultaneously raise good will, raise the customer experience and raise the overall efficiency of the business. At the former company, every employee understands the value of relationship capital as much as they understand the value of the company’s performance. Meanwhile, at the latter company, instead of looking at the negative effect of cost of delay, the negative effect of not offering their best "deal" up-front, and the negative effect of blatant classism, they artificially construct a workplace where employees are more worried about being "stingy" with what they offer customers, and then flaunt their lack of service with cold reminders of the service they’re not giving and go out of their way to be patronizing about the limited service they do provide.

So… Now for the reveal.

The first company is Zappos. I blogged about Zappos and CEO Tony Hsieh’s book, "Delivering Happiness" about a year ago. Let me tell you in pictures about my visit to Zappos and why I’m so impressed with them. The descriptions to go along with those pictures tell the rest of the story. There’s so much to tell, and these shots don’t tell the half of it.

Starting from the moment you walk in the door at the reception area, you know you’re not in a typical operation. The space is raucous. The guys behind the desks are handing out bottles of water, playfully joshing the guests on anything they can quickly turn into fun, running friendly competitions among the visitors and staff, and cutting the ties of unsuspecting (but should have known better) visitors. In a sitting area behind where this photo was taken is the company library where a QR code will take you to their recommended reading list.

Starting from the moment you walk in the door at the reception area, you know you’re not in a typical operation. The space is raucous. The guys behind the desks are handing out bottles of water, playfully joshing the guests on anything they can quickly turn into fun, running friendly competitions among the visitors and staff, and cutting the ties of unsuspecting (but should have known better) visitors. In a sitting area behind where this photo was taken is the company library where a QR code will take you to their recommended reading list.

While our effusive, outgoing, bright-eyed tour guide, Renea, happens to be in the middle of this shot, she’s not what I’m actually focusing on. It’s what happens to be directly behind her head. The office of the company’s goal coach. You have a goal? The goal coach’s job is to help you reach it. Personal? Professional? Educational? No matter. The goal coach’s job is just that: coach people to help them achieve their goals. No bounds, no strings, no pre-set expectations. Just positive goals.

While our effusive, outgoing, bright-eyed tour guide, Renea, happens to be in the middle of this shot, she’s not what I’m actually focusing on. It’s what happens to be directly behind her head. The office of the company’s goal coach. You have a goal? The goal coach’s job is to help you reach it. Personal? Professional? Educational? No matter. The goal coach’s job is just that: coach people to help them achieve their goals. No bounds, no strings, no pre-set expectations. Just positive goals.

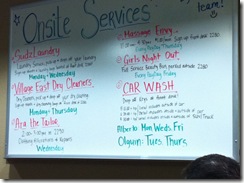

Real life doesn’t have a "pause" button. Zappos gets that. So, to help with "real life" while work life intrudes, Zappos has a continually evolving set of services it makes available to its employees to help minimize the inconvenience of being at work when "real life" must go on. Notice that most (if not all) of these services are not necessarily free. But they are convenient, and in some cases, they are discounted through group negotiations. Whether any are actually subsidized by the company, I don’t know, but that’s not important.

Real life doesn’t have a "pause" button. Zappos gets that. So, to help with "real life" while work life intrudes, Zappos has a continually evolving set of services it makes available to its employees to help minimize the inconvenience of being at work when "real life" must go on. Notice that most (if not all) of these services are not necessarily free. But they are convenient, and in some cases, they are discounted through group negotiations. Whether any are actually subsidized by the company, I don’t know, but that’s not important.

One thing to note, however, is that the company cafe is highly subsidized with all but hot, prepared foods being free or nearly free, and the hot entrees are very inexpensive. All with as much attention to nutrition and dietary needs as to taste and convenience. I don’t have a picture of the cafe.

This shot might just about say it all, if you really read into the statement being made at the company. Many companies have a hallway where they post their ongoing achievements. Zappos has such a wall, but theirs has something you don’t see everywhere. The top row of framed images are various financial (usually sales) achievements (pretty common). Also on this top row are included related achievements such as volume of transactions. In particular, phone call orders processes in a single day — in total, when supplemented by people whose primary jobs are not to take calls (not as common). The bottom row of framed items are copies of the company’s annual "year book". Only at Zappos, this year book is about the company’s culture. Every employee, every year, is encouraged to submit an original work in any format describing their experience with the Zappos culture. Good, bad, or pretty, or ugly. Everything is open and transparent and everything is published unedited. (Not common at all!) This is why I said that this shot might "say it all". The company celebrates its ongoing cultural achievements with the same enthusiasm as it celebrates its financial and operational accomplishments.

This shot might just about say it all, if you really read into the statement being made at the company. Many companies have a hallway where they post their ongoing achievements. Zappos has such a wall, but theirs has something you don’t see everywhere. The top row of framed images are various financial (usually sales) achievements (pretty common). Also on this top row are included related achievements such as volume of transactions. In particular, phone call orders processes in a single day — in total, when supplemented by people whose primary jobs are not to take calls (not as common). The bottom row of framed items are copies of the company’s annual "year book". Only at Zappos, this year book is about the company’s culture. Every employee, every year, is encouraged to submit an original work in any format describing their experience with the Zappos culture. Good, bad, or pretty, or ugly. Everything is open and transparent and everything is published unedited. (Not common at all!) This is why I said that this shot might "say it all". The company celebrates its ongoing cultural achievements with the same enthusiasm as it celebrates its financial and operational accomplishments.

To me, the fact that the incredible accomplishment noted on the left-hand-side of this picture is still nothing more than something printed on office paper six months after the event tells me that their celebration of success is both understated and not so high a priority — as in many other businesses — as to cause anyone to go out of their way to rush a costly picture onto the wall. You can also see here that this accomplishment is celebrated as much — if not more — for its reflection of the work put into it as it is for the financial results it caused. Also visible in this shot are a couple of the author-signed books given to Zappos CEO on behalf of the company. They’re not in his personal collection.

To me, the fact that the incredible accomplishment noted on the left-hand-side of this picture is still nothing more than something printed on office paper six months after the event tells me that their celebration of success is both understated and not so high a priority — as in many other businesses — as to cause anyone to go out of their way to rush a costly picture onto the wall. You can also see here that this accomplishment is celebrated as much — if not more — for its reflection of the work put into it as it is for the financial results it caused. Also visible in this shot are a couple of the author-signed books given to Zappos CEO on behalf of the company. They’re not in his personal collection.

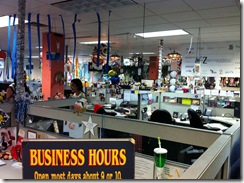

Every work team at Zappos is encouraged to decorate their spaces in their own way. Groups typically decide on a theme and the themes change from space to space. This image is of the team of people who work to decide what products to sell at Zappos, ("merchandising"). If you look in the center of the image, you may see what appears to be a dark green area. That’s the short row of cubes where the C-level executives of Zappos have their desks. Called, "Monkey Row", the next image is a close-up of this area.

Every work team at Zappos is encouraged to decorate their spaces in their own way. Groups typically decide on a theme and the themes change from space to space. This image is of the team of people who work to decide what products to sell at Zappos, ("merchandising"). If you look in the center of the image, you may see what appears to be a dark green area. That’s the short row of cubes where the C-level executives of Zappos have their desks. Called, "Monkey Row", the next image is a close-up of this area.

The anthropomorphic glove sits on the divider between the executive assistant’s  area in the foreground, and the CEO’s cube, behind the glove. The COO and CFO’s spaces are on the right with a conference room in the back. This day, all the C-levels are elsewhere.

area in the foreground, and the CEO’s cube, behind the glove. The COO and CFO’s spaces are on the right with a conference room in the back. This day, all the C-levels are elsewhere.

These chicken heads are the company’s  "retail systems" group. A QR code on the outside wall instructed me to ask them to put on their masks and take a picture to win a prize. The caped, masked rubber bathtub duckie wasn’t nearly as priceless as this photo. One might wonder whether such disruptions were deleterious to productivity. In fact, the opposite has been found. The tours are scheduled, not ad hoc. The employees are encouraged to take a break, interact and be friendly and welcoming to the visitors. There are only four tours a day and only on certain days, and the entire "disruption" lasts a few minutes. Fun and weirdness are both important and so the company creates opportunities for both. Zappos is an amazingly productive place.

"retail systems" group. A QR code on the outside wall instructed me to ask them to put on their masks and take a picture to win a prize. The caped, masked rubber bathtub duckie wasn’t nearly as priceless as this photo. One might wonder whether such disruptions were deleterious to productivity. In fact, the opposite has been found. The tours are scheduled, not ad hoc. The employees are encouraged to take a break, interact and be friendly and welcoming to the visitors. There are only four tours a day and only on certain days, and the entire "disruption" lasts a few minutes. Fun and weirdness are both important and so the company creates opportunities for both. Zappos is an amazingly productive place.

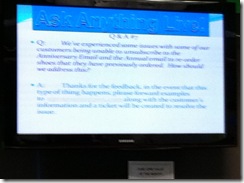

Communication is at a premium in Zappos. Here were see an example of a screen where questions and answers are posted continuously on customer and other issues resolved throughout the company. Nearby, we see an example of one of the many ways in which employees are reminded of the company’s core values. A new value is chosen for emphasis each month as a means of generating ideas and making progress towards common goals as a group.

Communication is at a premium in Zappos. Here were see an example of a screen where questions and answers are posted continuously on customer and other issues resolved throughout the company. Nearby, we see an example of one of the many ways in which employees are reminded of the company’s core values. A new value is chosen for emphasis each month as a means of generating ideas and making progress towards common goals as a group.

When you read the company’s list of core values, you see they show up in everything their people do. They’re not necessarily formally measured by how they "stack up" against these statements, but they are continually grounded in whether or not their actions are consistent with the values. While promoting a particular value each month may seem hollow, what makes it meaningful is that each employee is encouraged to express their manifestation of these values in however they believe they can contribute — as long as it’s consistent with the other values.

When you read the company’s list of core values, you see they show up in everything their people do. They’re not necessarily formally measured by how they "stack up" against these statements, but they are continually grounded in whether or not their actions are consistent with the values. While promoting a particular value each month may seem hollow, what makes it meaningful is that each employee is encouraged to express their manifestation of these values in however they believe they can contribute — as long as it’s consistent with the other values.

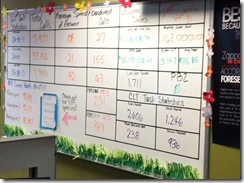

Let’s switch gears to metrics. One might conclude that a company with the sort of values linked above might minimize or eschew the use of metrics. One would conclude such things erroneously. Zappos is famous for, among other reasons, their willful bucking of industry norms by not forcing time quotas for how quickly people are expected to handle phone and text chat inquiries. Not using quotas and stop-watches running for each call, and not rewarding call-handling in terms of calls per hour may sound like the company doesn’t use metrics, nothing could be further from reality. The company devours metrics. They just don’t use them for petty, demoralizing, and customer-infuriating reasons. They use them to manage capacity and availability. In other words, they use them to ensure they have enough staff to handle their workload and to keep customer service levels as high as they can push them. These measures are directly across the entryway to the call-center area, not in some manager’s area. Besides, the manager would be sitting among the team anyway. Everyone knows the measures and no one has any reason not to use them.

Let’s switch gears to metrics. One might conclude that a company with the sort of values linked above might minimize or eschew the use of metrics. One would conclude such things erroneously. Zappos is famous for, among other reasons, their willful bucking of industry norms by not forcing time quotas for how quickly people are expected to handle phone and text chat inquiries. Not using quotas and stop-watches running for each call, and not rewarding call-handling in terms of calls per hour may sound like the company doesn’t use metrics, nothing could be further from reality. The company devours metrics. They just don’t use them for petty, demoralizing, and customer-infuriating reasons. They use them to manage capacity and availability. In other words, they use them to ensure they have enough staff to handle their workload and to keep customer service levels as high as they can push them. These measures are directly across the entryway to the call-center area, not in some manager’s area. Besides, the manager would be sitting among the team anyway. Everyone knows the measures and no one has any reason not to use them.

This whole area (most of the floor) is called the "CLT" for "customer loyalty team". They take the calls, operate online chat, and are just about the entirety of the live, human, customer-facing operation. But the group of desks in this shot are one of the most impressive investments I’ve seen anywhere. Zappos has a name for them, I believe it’s "Resource Team", but I call them the "slack team". Very simply, these people have full time jobs to go help anyone else anywhere else for any reason and for any amount of time. In other words, they take up the slack to keep things running smoothly. In most other operations, such jobs are "other duties as assigned" to people who already have jobs. In other operations, this sort of work is why people work late. At Zappos, these people work a regular work day doing nothing but making sure everyone else can work a regular work day — among other things.

This whole area (most of the floor) is called the "CLT" for "customer loyalty team". They take the calls, operate online chat, and are just about the entirety of the live, human, customer-facing operation. But the group of desks in this shot are one of the most impressive investments I’ve seen anywhere. Zappos has a name for them, I believe it’s "Resource Team", but I call them the "slack team". Very simply, these people have full time jobs to go help anyone else anywhere else for any reason and for any amount of time. In other words, they take up the slack to keep things running smoothly. In most other operations, such jobs are "other duties as assigned" to people who already have jobs. In other operations, this sort of work is why people work late. At Zappos, these people work a regular work day doing nothing but making sure everyone else can work a regular work day — among other things.

This is the last of my Zappos shots and the end of my Zappos explanation-by-pictures on just how deeply Zappos internalizes the needs of their customers. In this view we see an entire team dedicated to responding to inquiries made directly to the Zappos CEO, who’s made his email address, Twitter, and Facebook identities public knowledge. While Tony reads all his mail, responding is another matter. These people do nothing but respond to incoming messages for Tony — making no attempt to hide that they’re not Tony as we’ve seen in some businesses. While Tony does read and sometimes responds to his own mail and tweets, he can’t expect to get to a fraction of it. This group helps him manage all that.

This is the last of my Zappos shots and the end of my Zappos explanation-by-pictures on just how deeply Zappos internalizes the needs of their customers. In this view we see an entire team dedicated to responding to inquiries made directly to the Zappos CEO, who’s made his email address, Twitter, and Facebook identities public knowledge. While Tony reads all his mail, responding is another matter. These people do nothing but respond to incoming messages for Tony — making no attempt to hide that they’re not Tony as we’ve seen in some businesses. While Tony does read and sometimes responds to his own mail and tweets, he can’t expect to get to a fraction of it. This group helps him manage all that.

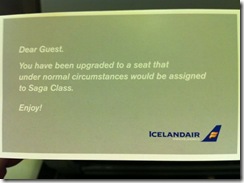

And now we come to the "other" company. The second company is an airline. The pictures give away which one. There really only need to be the two pictures because just these two convey so much.

This card was sitting on the arm-rest between the two seats where I was seated. I guess they reconfigured this plane to two classes because my ticket was bought in the next lower class called "Economy Comfort", but I didn’t see that class of seat on the plane. Only this ("Saga" class, i.e., "business class") and economy. But it seems this card is designed to warm me that they plan to treat me as though I’m in economy. In other words, they went out of their way to ensure one row of people — all of 4 seats — knew they were being excluded from the remaining 18 seats in the same cabin! They actually spent money to be inefficient AND lose all credibility with good will and a service attitude!

This card was sitting on the arm-rest between the two seats where I was seated. I guess they reconfigured this plane to two classes because my ticket was bought in the next lower class called "Economy Comfort", but I didn’t see that class of seat on the plane. Only this ("Saga" class, i.e., "business class") and economy. But it seems this card is designed to warm me that they plan to treat me as though I’m in economy. In other words, they went out of their way to ensure one row of people — all of 4 seats — knew they were being excluded from the remaining 18 seats in the same cabin! They actually spent money to be inefficient AND lose all credibility with good will and a service attitude!

In this next image you see that they bothered to put a sign on the headrest in front of this row just in case the card wasn’t clear: "You’re not wanted here and we’ll make sure you know it." How must it feel to be an employee told to visibly treat people as unwanted directly before their own eyes?! To offer headsets, champagne, gifts, menus with choices, and hot towels to people then stop short of offering the same to people inches away?! I’d feel ridiculous and I’d probably go home with an ulcer.

In this next image you see that they bothered to put a sign on the headrest in front of this row just in case the card wasn’t clear: "You’re not wanted here and we’ll make sure you know it." How must it feel to be an employee told to visibly treat people as unwanted directly before their own eyes?! To offer headsets, champagne, gifts, menus with choices, and hot towels to people then stop short of offering the same to people inches away?! I’d feel ridiculous and I’d probably go home with an ulcer.

Behavioral and psychological differences aside, do they have any idea how inefficient treating one row differently from the remainder of an entire cabin is? Clearly not. The transaction costs are obviously unknown. No wonder their banks failed.

What the pics don’t tell is the story of what took place in the terminal for nearly an hour before we boarded late. Starting 30 minutes before boarding, announcements began to be broadcast seeking two volunteers to give up their seats in exchange for business class seats the following day from a different city — a city the volunteers would have to fly to, presumably the next day as well, and, presumably on the airline’s account but on another airline.

Twenty minutes after boarding was to have started, they began to "sweeten the offer" with adding that the volunteers would receive one round-trip ticket anywhere the airline flew, and meal and hotel vouchers for their immediate over-night stay. It took another 15 minutes before they had their volunteers, and, I do not know what the actual final "deal" was — whether the volunteers took the announced deal or made a counter-offer. I do know that had my plans allowed me make such a last-minute change, I would have had a much more appealing offer to counter with. But that’s neither here nor there.

What’s wrong with this picture?

Is there anything right with this picture?

Does anyone believe there’s no relationship between the failure to make a compelling offer in time to keep the flight on time and the notes and signs and behaviors moments later exhibited on-board? Does anyone believe there’s no relationship between these events and the misconfiguration of the aircraft for the seats sold?

Did anyone at the company notice that they actually spent money to work-around this known issue rather than to simply go all-the-way and give the "upgraded" seat-sitters the full business-class treatment? Did anyone there notice how much inefficiency they incurred? Multiple meals, multiple amenities, multiple passes through the same place for different reasons? They even handed us different headsets! The flight attendants from the main cabin had to come through the curtain to give us our drinks and meals! For ONE row!

What about the sum of all these and the economics of having to divide how a single set of staff split their behavior, their resources, and their services within the confines of the same cabin? All for the sake of treating a single row of four seats differently from the remaining 18 seats? Any wonder that they’ve cut routes and scaled back others? Aircraft space is at a premium. It would have been much easier, not to mention far more enrolling to everyone, to have the entire cabin treated as the same class.

What makes this experience noteworthy is just how far out of norms it is. While many airlines go out of their way to find efficiencies, this one seems to go the other way. While many airlines take some pride in being able to treat some customers to upgrades, this one goes out of its way to remind customers they’re clearly not welcomed. Sadly, it’s also noteworthy that there doesn’t seem to be much the staff can do about any of it. This is clearly how the company wants the operation to run. They go out of their way to build the system so that it runs this way.

Little did I know at the time, but upon arrival in the country, I learned that some of the pilots of this airline have decided to "strike" and not fly. Without warning. Not as part of an organized effort, but on their own. While in the US, this would never work for companies based there, it seems to be common in more socialist economies like in Europe. Let’s look at what causes a company’s people to strike: um… problems with their employer!

As a result, a number of invited guests are not going to make it to the event and other are delayed indefinitely and may miss the events here entirely. With the experience fresh in my mind (and ongoing), I tapped out most of the text of this post while in flight. I had not idea about the strike. But I could not have imagined a more appropriate demonstration of the negative and permeating affects of bad policy. Clearly, the striking pilots are not happy about how they’re being treated.

I’m sure there will be executive blow-hards at this company and elsewhere quick to say that they have nothing in common. That how my experience in the terminal and ob-board have nothing to do with the pilots’ gripes. I, Zappos, and those of us who see the connection between company culture, employee satisfaction, and customer satisfaction would vehemently disagree.

Zappos could teach these people a lot. No wonder people have suggested to Tony that Zappos starts an airline. Though… there already is one Southwest and both Zappos and I love them.

[Note: lest anyone think that the actions and behaviors and attitudes I note are just me and my "Western sensitivities" to class structures, I should point out a number of things: I fly enough to fly in business and first class a lot-- both by upgrades as well as by purchasing the appropriate fares. It doesn't bother me when I'm in a more economical class and the more expensive classes get better service. In those situations, the airlines at least do what they can to separate the service classes, and besides, I know what I've gotten myself into and the airlines don't rub it in my face. Furthermore, the European guy next to me had the exact same impressions... All the way from the volunteer fiasco to the notes and signs to the differences in treatment.]

Counting Change

Posted by agilecmmi on May 2, 2011 in Change, Defects, Discipline, Engineering, Performance, analysis, legacy, maintenance, measuring, operations, review, technical | Comments Off

A more appropriate title would have been "counting changes" but it would have hardly been as interesting. ![]()

Change happens. And often.

In particular, when a product is in its operation and maintenance ("O&M") phase, changes are constant. (Note: O&M is frequently called "production", and this simple choice of words may also be part of the issue.) But, too often, changes to products are handled as afterthoughts. When handled as "afterthoughts", product features and functions receive far less discipline and attention than warranted by the the magnitude of the change were the new or different feature/functionality have been introduced during the original product development phase.

In other words, treating real development as one would treat a simple update just because the development is happening while the product is in production is a mistake. However, it’s a mistake that can be easily diffused and reversed.

O&M work has technical effort involved. Just because you’re "only" making changes to existing products that have already been designed, does not mean that there aren’t design-related tasks necessary to make the changes in the O&M requests. Ignoring the engineering perspective of changes just because you didn’t do the original design or because the original (lion’s share of) design, integration and verification work were done a while back doesn’t mean you don’t have engineering tasks ahead of you.

In O&M, analysis is still needed to ensure there really aren’t more serious changes or impacts resulting from the changes. In O&M, technical information needs to be updated so that they are current with the product. In business process software, much of the O&M has to do with forms and reports. Even when creating/modifying forms, while there may not be any technical work, per se, there is design work in the UI. The form or report itself. And even if you didn’t do that UI design work, you still need to ensure that the new form can accept the data being rendered to it (or vice-versa: the data can be fit into the report).

It’s frightening, when you think about it, how much of the products we use every day — and many more products that we don’t know about that are used by government and industry 24/7 — are actually "developed" while in the "O&M" phase of the product life cycle when the disciplines of new product development are often tossed out the door with the packing material the original product came in. Get that? Many products are developed while in the "official" O&M phase, but when that happens they’re not created with the same technical acumen as when the product is initially developed.

(I have more on this topic, and how to deal with business operations for products in the O&M phase, in this Advisor article from the Cutter consortium.)

In a sadly high number of operations I’ve encountered, once a product is put into production, i.e., is in O&M, the developers assigned to work on it aren’t top-notch. Even in those organizations where such deleterious decision-paths aren’t chosen, the common experience in many organizations is that the developers are relied-upon even more for their intimate knowledge of the product and the product’s documented functionality — as would have otherwise been captured in designs, specifications, tests and similar work artifacts of new product development. In these organizations, the only way to know the current state of the product is to know the product. And, the only way to fix things when they go wrong is to pull together enough people who retain knowledge of the product and sift through their collective memories. The common work artifacts of new product development are frequently left to rot once the product is in O&M, and what’s worse is that the people working on the new/changed features and functionality don’t do the same level of review or analysis that would have been done were the functionality or other changes been in-work when the product was originally developed. Of course, it’s rather challenging to conduct reviews or analysis when the product definition only exists as distributed among people’s heads. Can you begin to see the compounding technical debt this is causing?

I’ve actually heard developers working on legacy products question the benefits of technical analysis and reviews for their product! As though their work is any more immune to defect-inducing mistakes than the work of the new product developers. What’s worse is that without the reviews and analyses, defect data to support such a rose-colored view seldom exists! It’s entirely likely, instead, that were such data about in-process defects (e.g., mistakes in logic, design, failing to account for other consequences) to be collected and analyzed, it would uncover a strong concentration of defects resulting from insufficient analysis that should have happened before the O&M changes were being made.

Except in cases where O&M activities are fundamentally not making any changes to form, fit, feature, appearance, organization, integrity, performance, complexity, usability or function of the product, there should be engineering analysis. For that matter, what the heck are people doing in O&M if they’re not making any changes to form, fit, feature, appearance, organization, integrity, performance, complexity, usability or function of the product?!

If anyone still believes O&M work doesn’t involve engineering, then they might need to check their definition of O&M. Changes to product are happening and they’d better be counted because if not, such thinking fools organizations into believing their field failures aren’t related to this. Changes count as technical work and should be treated as such.

(I have more on this topic, including how to help treat O&M and development with more consistent technical acumen in this Advisor article from the Cutter consortium.)